How I Did John Cassaday Wrong (and Strange Stuff: The Beauty of Planetary)

“With John Cassaday’s background in audiovisual film/television work, this makes Planetary exemplary decompression comics and a welcoming mature balance of gekiga and cinematic time.”

- from an untitled essay in progress

John Cassaday has passed on, far far too young, and I have been delaying writing about how good his work can be, because I was focused on the (talented, but less than scrupulous) writers he sometimes worked with.

That was not only me. This is a common problem with writers writing on writers, with criticism on the whole.

John Cassaday did nothing wrong, and suffered for the wrongs of others.

In the future, I’ll have what I’ve been calling My Last Planetary Reread, but truth is, it won’t be the last time I reread it. It will never be the last time I think about it. Never the last time I see his art, with my eyes or in my brain.

John Cassaday put a flower in my brain, intricate and blunt, beautiful, abstract, frightening and big, and its petals and planes are uncountable.

What follows is an essay I wrote for the Comics Cube, which Duy Tano edited, and is reprinted here with his permission.

When I wrote it, other Cube contributors were going to add as much as me, or more, to sections, which fell apart the way some good things do. What was left was me, dealing with my grandmother’s death, my grandfather’s impending, and a lot of stress and misery and beauty and hope and stacks of comics, including the big nice hard cover omnibus of Planetary.

Strange Stuff: The Beauty of Planetary

Travis Hedge Coke

To those who are gone. Those we were glad to see go, those we wish a swift return, and those we will wait forever to see again.

“I didn’t want them to go away.”

Elijah Snow, in the land of the dead

Planetary #23, “Death Machine Telemetry”

Planetary is one of the best comics to ever exist. Go check some out. Do an image search, buy a ten dollar digital of the first collection, plunk down for the omnibus. Planetary is so good, I will put it up against future comics that haven’t even been committed yet. I will weigh Planetary, sight unseen, against any untested opponent. It’s not my favorite comic, but it is a comic that always excites and delights me, whenever I reread even a few panels, an issue or a scene.

So, why do its most ardent fans seem, so often, to want to limit its range or glory? How is it, that it is hard to find essays praisingPlanetarythat do not also spend much of their space explaining what the comic did wrong, or which issues are superfluous?

Julian Darius, in the essay, Appendix: Sequencing Planetary from Keeping the World Strange, spends much effort on rearranging the order in which the comic is told, to fit the order in which events occurred, that when he addresses a master spy giving a piece of information to our heroes as being perhaps unnecessary, he seems to have missed that the effects of giving them that information, and of them accepting it from him, benefit for them and him. Simple social politics and old-fashioned trap-setting go unacknowledged, to present this situation as a misstep. Attendant to this, Darius claims that chapter must take place after those that were published following it, because a major event is unmentioned in those, despite characters in the comic, itself, discussing how (and why) that information was not being thrown casually about.

There are some things that don’t seem to agree with themselves, in Planetary. There are, perhaps, some flaws. But, “I kidnapped an important man and am hiding and torturing him, and therefore do not tell everyone I have him, or where” is not a flaw. It’s not an incongruity. It’s called keeping a secret.

Darius is smart, no doubt, and I am sure he lovesPlanetary. But, he must love it differently than I, to suggest, for example, that with a flashback to Elijah Snow’s youth immediately following the return of his memories, “there is no reason to let it interrupt the current-day issues.” Or, further, that any flashback issues, especially those presenting clues or material the current-day cast are unaware of are misplaced by coming before the current-day revelations. His other essay pairs his own determination that Planetary is “a reconstructionist work with revisionist themes” with Planetary’s writer, Warren Ellis’ self-description, “it’s about, as Alan Moore put it, ‘mad and beautiful ideas,’” saying before that, “Planetary will doubtless have its grim moments, and will certainly always have an atmosphere of mystery… as close to fun as I can get.”

If this is what Warren Ellis has set out to do, why try to excise the mystery, to rush answers? Why try to establish a distinct system of Revisionist and Reconstructionist comics and agendas, and bendPlanetaryinto it, or suggest the comic has failed when it does not fit one or the other so aptly?

What is wrong with “an atmosphere of mystery” or “mad and beautiful ideas”?

MAGIC

“The past makes you laugh and you can savor the magic”

– Lou Reed, Magic and Loss

One of the chapters of Planetary borrows the name of a grand Lou Reed album (and title song), Magic and Loss. Planetary is, more than anything (for me), about Magic, and about Loss, and it is about these things in an unflinching and constructive fashion. The comic is gorgeously, caringly Deconstructionist, and Warren Ellis is a determined Modernist (for me). For Darius, it was reconstructionist with revisionist themes. For you? Something true to you, I’d hope, whether or not it syncs with mine. The talent pool on Planetary were Modernist, Postmodern, compassionate, daring and they dissected, polished, sutured, and resurrected life itself and dreams plus quam perfectum on and between every page. It was not a realist or naturalist work, but it can, by turns, be carefully representational and eagerly abstract. Planetary is traced and built simultaneously, as earnest Deconstruction must be. While Deconstruction has been mistaken for destruction, and has been called synonymous with justice, for the sake of Planetary, Deconstruction is magic.

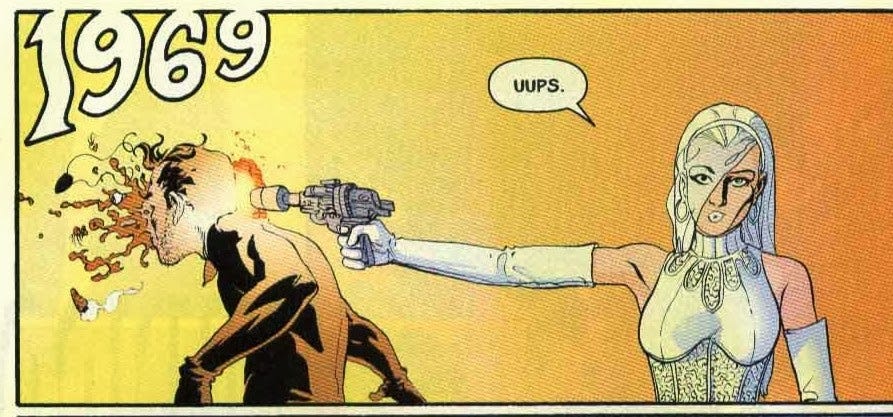

Part of a wave of mashup slash birdwatching comics, where everything could prove to be a reference, each character was an allusion, Planetary differs from other such animals by being determinedly not about specific versions of anything. It’s perfectly possible for one reader to see, in the chapter titled “Dead Gunfighters”, an extended study of the DC Comics property, the Spectre, or a bunch of riffs on Hong Kong heroic bloodshed movies, or a twenty-page story of grief and impossibility in a continuum of short stories about just those tropes, without seeing the other angles. The people who would recognize the Spectre with his chalk-white skin and green hood or shorts and those who can name the stars of dozens of HK shoot-em-ups aren’t necessary the same folks. We see our angle first.

Planetary presents for a model of the world, an exceptionally complex snowflake that presents an entire new reality when turned a bit or reexamined. Finding our angle, feeling our trajectory, does not denigrate or deny other approaches, other outcomes.

To present something as simple or childish is not the same as denying it, its glory. Alternately, to present the Great White Hunter or the myth of the Femme Fatale without acknowledging the weaknesses and suppositions that allow us to believe in them despite sense and evidence, would be unfair and unkind.Planetary, even when Elijah or his enemies are cold, is not unkind, never uncaring.

Planetary does not present to us any quintessential or specific James Bond or a purified and trueS uperman, but shows us, with different characters, at different moments, in different ways, whatJames Bondcan feel like, at best or at worst, what Superman does to us and for us. When Dracula appears, he is called Dracula, he is obviously Dracula, but he doesn’t suck anyone’s blood, he doesn’t quote Stoker, he laments his treatment by his inferiors and is generally an aristo-elitist horror. The focus, when Carlton Marvell is introduced, the John Carter riff who adventures on faraway planets and loves exuberantly, is not reduced to four-armed green men pastiches, but embodied by him standing on a plateau, looking to the sky, to places he may be forever denied, beauties he may never again touch. Dracula is the horror of self-righteous landlords, John Carter about, here, magic and loss, sacrifice and yearning appreciation.

Perceived Systems

“You’ll start from zero over and over again”

– Ibid.

Readers and critics are often eager to talk about systems and organization inPlanetary; is this special canon, is this Superman riff more Superman than this one, when Elijah says he, Jakita, and The Drummer represent three different systems, what does he mean? Categorization is helpful to analysis, but all maps are artificial, and we would do well to remember that. The principal villain, Randall Dowling, says at some point, “We are very old,” and he is, indeed, older than he physically appears, but he says it to Elijah Snow, who is even older. The category of Old only serves you so far.

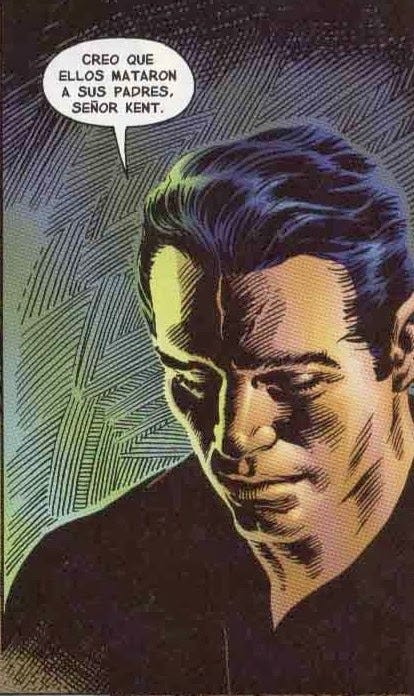

Jakita Wagner can be categorized as a Superman, from one angle (doomed high-science society, orphan survivor sent to our world, raised by farmers, strong and fast and just), as are the nameless blue baby Dowling’s people murder, and the caped mess shot to death in “To Be in England, in the Summertime”, the sharp against the sun silhouette from the same chapter, the blond farmland-raised New Deal godman called The High, and Clark Kent, himself, in the “Terra Occulta” story. But, too, in “Terra Occulta”, Jakita is paralleled by Wonder Woman, Diana Prince, who takes her role in the three-person team and mirrors her life in terms, too, of being the last survivor of a destroyed society, with her aristocratic inheritance and exceptional physique. Rigidity, here, is not our friend.

Jakita Wagner, Anna Hark, and William Leather are all children of Century Babies, except that Jakita has to be the child of one who she isn’t working with, Anna is also the inheritor of an older trust, and William Leather is not, actually, descended from the Century Baby whose name he inherited, which rankles him to no end. From that common springboard, we see Jakita act almost free of social inheritance, Anna hold dear to her familial duties and responsibility to the world, and William seek the heights of power he feels he is being unfairly denied as a bastard.

And, the Century Baby system, too, is muddled. People born at the turn of each century, they embody certain elevated traits, live extended lives, and are not entirely human. They are the white blood cells of existence, the healing and defense mechanism of reality. One might be the Spirit of the Century or the Ghost, live precisely one hundred years or be murdered en masse days after their collective birthday, at forty-five. The same entity that claims they have no souls is presumably the one who lies to a ghost in Hong Kong, informing him there is no Heaven or Hell or any afterlife, to motivate his worldly vengeance. So, too, this trait of the Century Baby is suspect.

The X-Files-style conspiracy chapter, “Zero Point”, with its flying saucer and death ray, is also the one with the hammer from Marvel Comics’ Thor. This hammer, is a walking stick that can turn into a fighting hammer of a god. Is it in this issue because in that Thor’s initial appearance he is in the midst of an alien invasion? Is this the chapter with the Professor X and the X-Men riff because they are so closely tied to alien encounters in the comics? Or are these things aligning themselves by chance, or by my perception?

Loose Threads

“There’s a door up ahead, not a wall”

– Ibid.

Everything in Planetary is suspect. Characters lie in Planetary or hold back truths. People act out of misinformation or misunderstanding. Apparent truths may be later overturned. And, when Elijah Snow says, “Where a thing does what it does according to the intention of the observer. This is my responsibility. This is my intent,” it is meant not only in-world, in-scene, but can be understood to dictate our responsibility as audience; Ellis, Cassaday, Martin, Baron, Jimenez, et al’s responsibility as authors. When we readPlanetary, we makePlanetary. When we thinkPlanetary, we re-author it.

Is that whyPlanetary, more than most comics, left a lot of mysteries wide open, or opened up what normally would not have been mysteries into something questionable? A big chunk of Keeping the World Strange, the critical analysis book on the comic, is people trying to find out what is or is not canon and Planetary does not make it easy on them. Or, it makes it too easy, because, look, it’s all canon. The stuff that embeds the comic into the WildStorm Universe, the shared universe of its publisher/imprint, is all as valid as the moments that encourage you to forget it’s part of a shared universe. The crossover with Batman (“Night on Earth”), or the crossover with Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman (“Terra Occulta”) are no more or less canonical or “in continuity,” than any single issue/chapter of the main series. From the very first pages of the comic, really, we are reminded again and again, that alternate realities are still reality. Experiences are valid, even the parts of them that are misinterpretation.

When Chad Nevett says, inApocrypha or Canon?, that “Terra Occulta” is “something that is a fun little detour that doesn’t actually relate to Planetaryin any meaningful way,” he dismisses that via justifying it by what it provides us in explanation about superpowers and in-world clarification, but what’s bigger than all that, to me, are the political and metaphoric extensions that it provides. We see, sharply, with our main cast made villains, how close they are, anyway, to being the villains of their own story. It is our trust in them, more than anything, that justifies Elijah’s comedy abuse of The Drummer or his coldness when the enemy murder an entire skyscraper above him and those closest to him, safe in a bunker below.

We see, in “Terra Occulta”, what greater commercial application of wonders like superspeed and teleportation looks like, but some are still unsatisfied, unsure it reaches enough people, does all it could do. And, as with our really real world, there always will be people who feel that technology is not available enough, not applied as well or as affordably as it could be. Stories need that, to drive them forward, and we live it, because we lack the agency to do (yet) do best.

But, “Terra Occulta” also provides itself with a seemingly unnecessary unanswered thread, when the heads of Planetary are defeated, except for one guy, who is never addressed in-story again. Why leave that hanging?

We are used to pay offs, in our fiction, for the ball to be thrown into the air so that sometime later it will come down. Chekhov’s Gun is a holy thing for us, whether we realize it or not. You can’t just pull a god out of a box or a machine gun out of the aether, without seeding it in the story early on, or people feel they have been cheated. And, if you introduce a gun on the mantle or a man on the edge of town, you better make use of them again before the finals lines are uttered.

Planetary, delightfully, leaves several balls in the air.

Spoilers, people. So much the spoilers. If you like, skip now to the next section.

In “Planet Fiction,” a team rocket to a fictional world and retrieve a fictional man, and after he kills a lot of them, he disappears from the comic. While readers waited, eagerly, for his return, what we get, instead, is Drummer asking about him, and Elijah suggesting he just went wherever he went. Other places. Probably other stories.

Fiction is not bounded, as reality may be. Nor, as our expectations most often are.

The primary villain of Planetary, Randall Dowling, messes with our main hero’s memories, and ostensibly he regains most of his faculties halfway through, but his memories, as we see them, or even what are ostensibly objective flashbacks, don’t seem to jibe with how other people talk about certain events. (Is that Antarctic base one of the enemy’s, or one of Planetary’s?) Are his recovered memories also muddled? Jakita suggests such, saying “your memory is incomplete,” and soon after, the always untrustworthy superspy, John Stone, helps Elijah to remember better, while also planting suggestions of his own. Eventually, Stone tells Elijah that not only was he subjected to memory manipulation, but that Dowling can stretch inside your brain, get in your head and think thoughts with or for you. That, anyone who has been near Dowling might be Dowling, never realizing they were thinking thoughts he put there, feeling things he plotted.

There’s no good evidence that when Elijah kills Randall Dowling, Dowling is not still inside Elijah’s head. No one acts on that threat. There is no sensible way to check it or counter it, so it goes ignored. But, if it’s true, the supervillain won. He yet lives. He yet thrives. The best Elijah can do, is to live as if it isn’t true, whether it is or not, and to do the best he can with his life. It is a huge thing to leave hanging, but it is best left suspended there. The sword of Damocles should not be touched too much.

Who does the superhero in “To Be in England, In the Summertime” think is writing the sick twists into his life? Do Elijah and Planetary really stop the decimation of the world by alternate reality horrors who think they own us? Is the origin story of the Earth, at the beginning of “Creation Songs” true? Is there an afterlife or isn’t there? Is there an evil presence hiding in even the best people in Planetary? What happened to the two members of the Four that Elijah let live? Did Elijah doom reality by turning on his time machine or not? How do the Hark family ensure the sun rises?

When the twenty-sixth issue originally came out, many of us thought that the appearance of a word, “ancestors” was a mistake, because we had seen both survivors of terrifying experiments in Science City Zero, and descendants, but never any ancestors. That word is still present in the omnibus edition that was recently released. It does not have to be a mistake. It can be a mystery.

Explorative Reach

“The strength to acknowledge it all”

– Ibid.

If I have a strong criticism of Warren Ellis’ work (it isn’t very strong and) it is that he sometimes plays it safe. I have heard Ellis’ work called “divisive” or “love it or hate it,” but he is a bestselling author of comics and prose for reasons, and those reasons do not include large percentages of the audience hating the work. He works to keep as much of an audience as he can, I think, and probably rightly so that he does. This can, however, lead to some slower or simpler moments than everyone likes, some easy routes taken.

Martin and Cassaday were explosions when they hit their stride, but their work since has been, while quality, in many ways predictable.

Joss Whedon says Ellis “gives us a… more cinematic frame” than Alan Moore, and I suppose it depends on how you take “cinematic,” but I don’t think so (take that Joss Whedon!). I think Warren Ellis is much more TV, or at least, TV screen, than he is in the theater cinematic. Alan Moore is the 7:20 p.m. showing in a semi-crowded theater downtown with semi-clean floors and only a little streaks in the projection, Warren Ellis is 2 a.m. televised broadcasts you understand in the special quiet hum of electrics and an otherwise empty living room. Except when they’re the reverse and Whedon is right, which can also happen.

Ellis paces, though, and shapes, based on a variety of media and delivery systems, implying TV screens, pulp renditions, documentary footage, grindhouses, Fifties poetry, t-shirt slogans, technical documents, and he often does it without aping the things, only giving us the hallmarks or tone. His best bit of pacing, in the script for the first issue, the chapter titled “All Over the World”, is when he stops the play by play of a big smackdown and writes directly to the artist, Cassaday: “John… It’s the Fight Scene, for god’s sakes, do with it what you can.” He shows his trust in Cassaday and his enthusiasm repeatedly in that script. Earlier in it, he writes, “this book was set up for you to go wild as much as any other reason, John.”

Planetary pulls out all the stops. The talent pool on this comic seem willing to try anything, to go anywhere, to focus in with astonishing precision and to spatter about madly in a dizzying mess of orchestrated chaos. It’s really beautiful how all the divergent techniques and amazing structures pull together inPlanetary. One chapter may have first person narration, another pages of illustrated prose, near-silent passages, unique panel borders or idiosyncratic panel arrangements, the chapters do not necessarily share a tone or pacing, molded, as they are, to the genre and subgenre concerns of their individual focus.

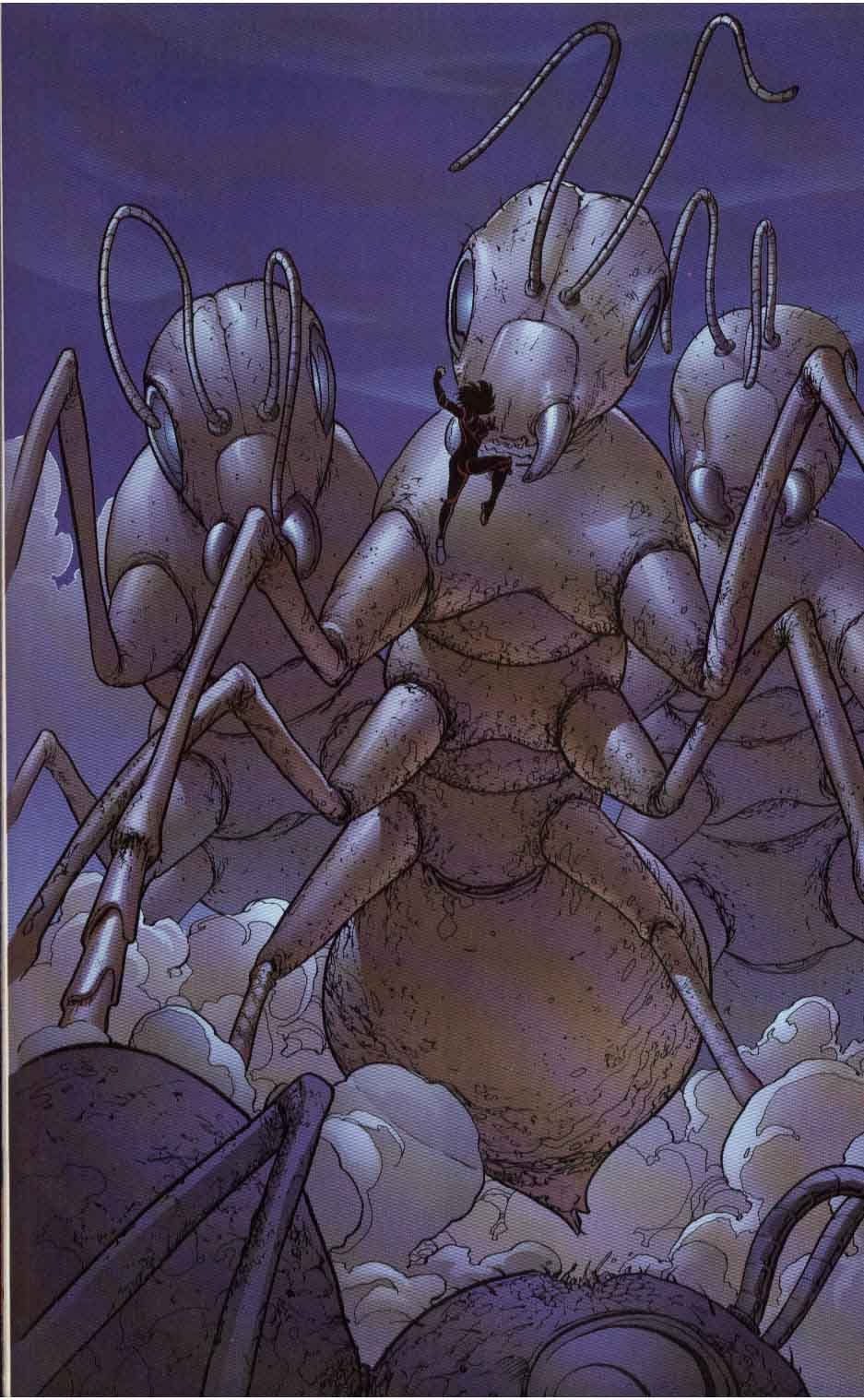

“Island” is a mashup of Yukio Mishima biography and entertainment, and giant monster movies typified by Toho productions of the Sixties and Seventies. It merges them glorifyingly and horrifyingly, but the next chapter, “Dead Gunfighters” is also strongly about a type of Asian cinema, the heroic bloodshed/honorable men gunfight movies of Hong Kong in the Eighties and Nineties, and it does not play out at all the same. The panels go from the blocky, big images that befit giant monsters and monstrous dreams, to sleek widescreen panels stacked to encourage a sense of motion picture stills and suspended action that explodes, when necessary, to full page splashes.

The prose pages in “The Good Doctor” reveal racism and self-loathing in the title character, Doctor Axel Brass, that his current-day portrayal does not, and yet they are the same man. These are not skippable pages, in the fashion of the prose support pages in Earth X or League of Extraordinary Gentlemen vol. 2. More than just being integral, they are in no doubt simply part of the story, part of the chapter.

Laura Martin can arouse a sense of reality or classicism simply with the variety of color she chooses to employ in a scene. John Cassaday knows how to evoke the Western or film noir, atomic horror or jus’ plain folks sitting at the table, without overly pastiching anything or any previous artist. I throw in Ellis’ name more often, as author, but these are collaborative comics, no doubt, and every one of them the author, even if DC owns the whole thing. John Cassaday knows how to tell a story. Laura Martin knows emotions and motion and wires up you brain, as you read her pages, with her choices and techniques. What she built off of David Baron’s gorgeous pure green or red filters in a handful of issues, and turned some of these into apparent codes or implications is remarkable.

The grids and constant visual and metaphoric echoes in “Death Machine Telemetry” are not novelty or there to suggest depth, but exist to make the story work, to make the comic do its job. Warren Ellis, with Planetary, is a master of Modernism, and he makes his associates so, at least for this comic. Planetary has jobs and each chapter, each individual issue as they were released, or taken now as a whole, must do those jobs efficaciously and truly. Those visual echoes must make the reader feel a certain way, pace their thoughts and understanding after a particular, engineered fashion. The newsreel sensibility of many scenes dealing with the Four, first in actual documentary recordings, and then simply in pacing or presentation, encourages the reader to understand the Four in a special way, different from how we understand the Spider, the island full of huge monsters, or adventures of a younger Elijah Snow, traveling the world and seeking mysteries.

Elijah Snow is not seeking answers, in Planetary, not unto themselves. He is pursuing mysteries.

Loss

“There are some things you have to throw out”

– Ibid.

Planetary, for me, is about three things: the Twentieth Century, the Bomb, and Death. Those are probably the same thing, in that they are big, inarguable, they hurt, and they are undeniably real.

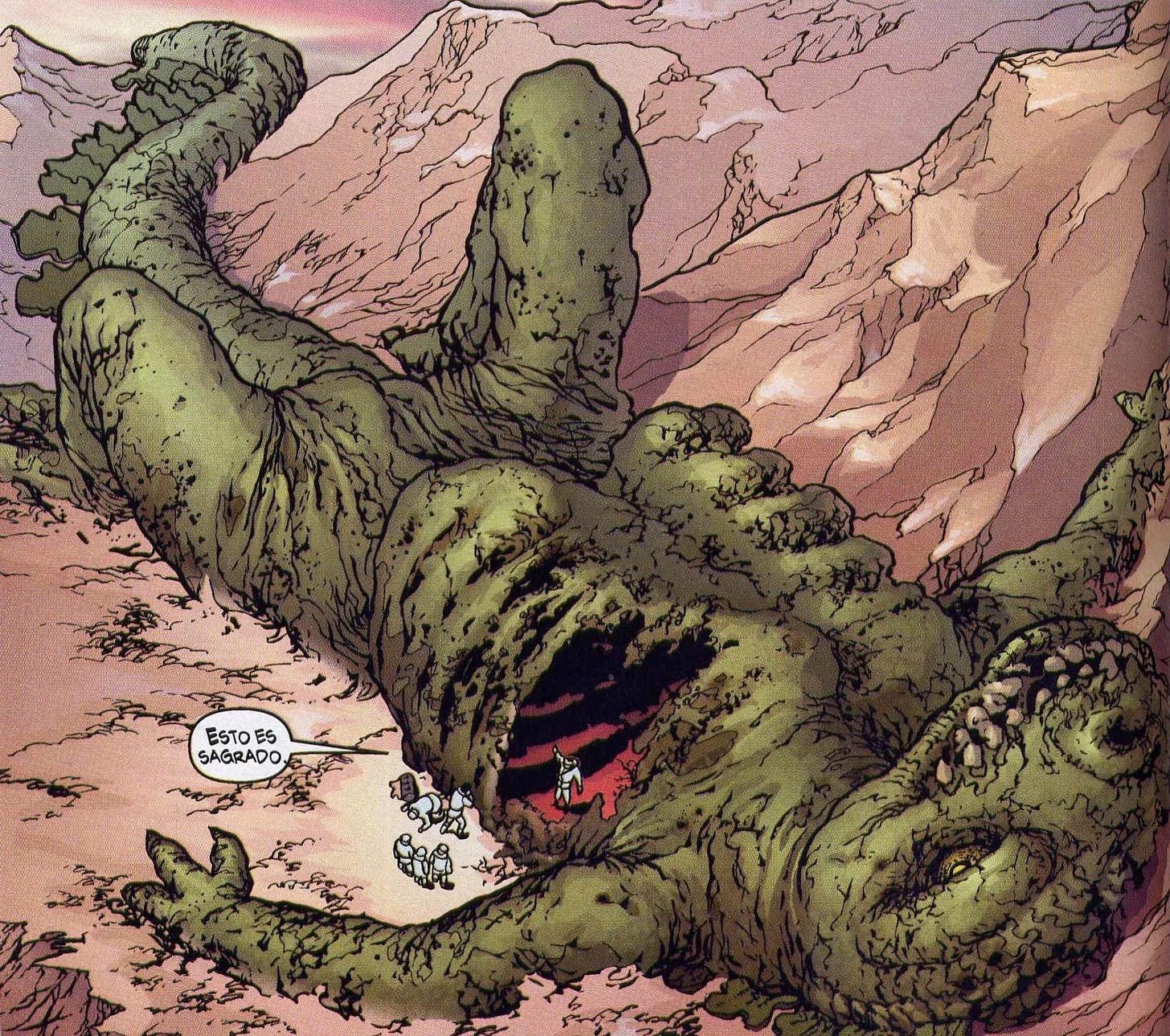

“Creation Songs” is the first Planetary chapter that I remember getting badly trounced on release. Up til then, everyone loved this comic, and suddenly, I was seeing “well, it doesn’t really add anything,” and “it’s so sparse.” There are, roughly, three distinct parts to the comic, and three distinct protagonists to the three stories in it, with the title not appearing until halfway through. The first part, is about the birth of the sun and the attendant rise of animals and stuff on Earth, overseen by ancient giants so old they mostly just lay around as mountains and big rocks, who sing the name for each thing in the world and go back to sleep. The second, is the story of Elijah Snow trying to make things right with the family of his best friend, a man he’d gotten killed, and then never dealt with because he’d been amnesiac and wandering around. The third story, taking up the second half of the chapter, is Elijah waking up one of the ancients and using him to hurt the enemies of Elijah and the man who murdered his friend.

In this chapter, we are shown the love the ancients have for their children, the animals and plants of Earth, including us. We see, next, the pride and love that Elijah has for the wife and daughter of his deceased friend, the pride and love that wife has for her dead husband and for her daughter, and the grief they all share for the man who is no longer present. Elijah tells the story of Carlton Marvell, an explorer standing alone on red rock, trying to use a sleeping giant to find a way behind reality, to the place where all things are dreamed from, all things are formed and sung. Elijah and his team are not good enough to reach his dead friend, here, or talented enough to talk with our cosmic ancestor, but, they can shake things up, they can wake up our ancestors by simply firing earnest, if nonsensical information at them. They can comfort the mourners and children, they can scare off the thieves and scavengers.

The chapter, “Creation Songs”, is about a hell of a lot. It is about death. It is about progress and care. It is, too, about great weapons and fierce tools and how little we really know how to do with them except hit things.

At least a third of the chapters in Planetary are concerned directly with what is called “atomic horror,” the genre or meta-genre of responses to the myth and reality of radioactivity and The Bomb. Whether radiation causes giant monsters or it is a giant monster is inconsequential when cities can be flattened. The science of an orbital death laser is not that of a hydrogen bomb, but it is still incredible heat and light ramming you horribly until nothing but blast shadows on broken concrete remains of anyone. The majority of the Twentieth Century is the shadow of the Bomb, a shadow cast both into the future from the blinding flare of the first tactical use, and back to the early visions of its range, its potential cruelty.

The Bomb is Death. Cancer caused (and sometimes cured) by radiation, by atomic horror, is Death. Godzilla and giant ants, Galactus, worldbombs, gunshot wounds are Death. “Time,” writes Warren Ellis, “is killing us all.”

I am very aware of death, I’m fairly comfortable with it, but I detest having friends out of range of a good, solid cell phone signal. Death, as Bob Dylan tries to remind us, is not the end, but it is the equivalent of the internet access going out for a very long time, with no definite return.

Planetary is about Death. Grief is potent and often immature, but it is a kind of immaturity that none of us will ever rise entirely out from, because it is the immaturity in which we are, by living, bound. The truest line inThe Princess Bride, a movie of a book about popular myths and people who died, is just “I want my father back, you son of a bitch.”

Planetary never did anything with pirates.