Flashback to an Old Review of Clive Barker Short Films

I used to write movie reviews.

I ghosted some for a county-wide newspaper, for awhile, under the name of their “star” critic; I’m sure not the only person to. I quit that gig when tasked with watching 2002’s Extreme Ops, a movie so bad, whose delayed release was still so badly timed, that I walked out midway, knowing I could be fired, and firing was preferable to seeing the rest of the picture.

Later, I wrote for GAS, the G____ Art Show, for about two years.

I fake proposed in one of them, to someone who was in on that from the start. Proposing to someone in a public, especially in a commercial and public forum, is manipulative. We were watching the movie and thought it would make the review better. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Adventures in the Ojai Underground, as mentioned in this review, is a satire of boys adventure & buddy comedy movies. We were reading a lot of William Burroughs and Kathy Acker at the time, and looking at Goonies, Red Dawn, and 48 Hrs. though that kind of parade.

Below is one of the GAS reviews, covering Clive Barker’s short films, Salome and The Forbidden, which Redemption released on VHS in the ol’ VHS days.

Happy to say my “moviemaking career” did not stop where I thought it might, in this review. Sometimes things work out.

Review of Clive Barker's Salome and The Forbidden

I'm fascinated by filmmaker's student or pre-hit works. I've watched student film festivals where everything looks like a slower version of a Quentin Tarantino scene or a more obtuse take on Peter Greenaway techniques. But, you get fabulous stuff, too, that reveal more than only influences, that reveal more than, perhaps, the film's talent, themselves, understood. My entire career in movies and television was during my “student years,” and outside of cutting together a new version of Meaningless (don't worry, you pr'y never saw the previous edit) later this year, that may easily be the whole of that career. But, when Mixing Bowl Studios decided to put an un-cleaned-up version of Adventures in the Ojai Underground on YouTube as a teaser, I heard some of the talent suggest it presaged and outcooled their professional work since we made that in high school. Sort of like THX 1138 compared to George Lucas' later works, or – if you are being cynical enough – Dementia 13 when seen through the lens of Godfather III. Vincent may not be the best Tim Burton movie ever, but there is an easy argument to be made that it is one of the purest.

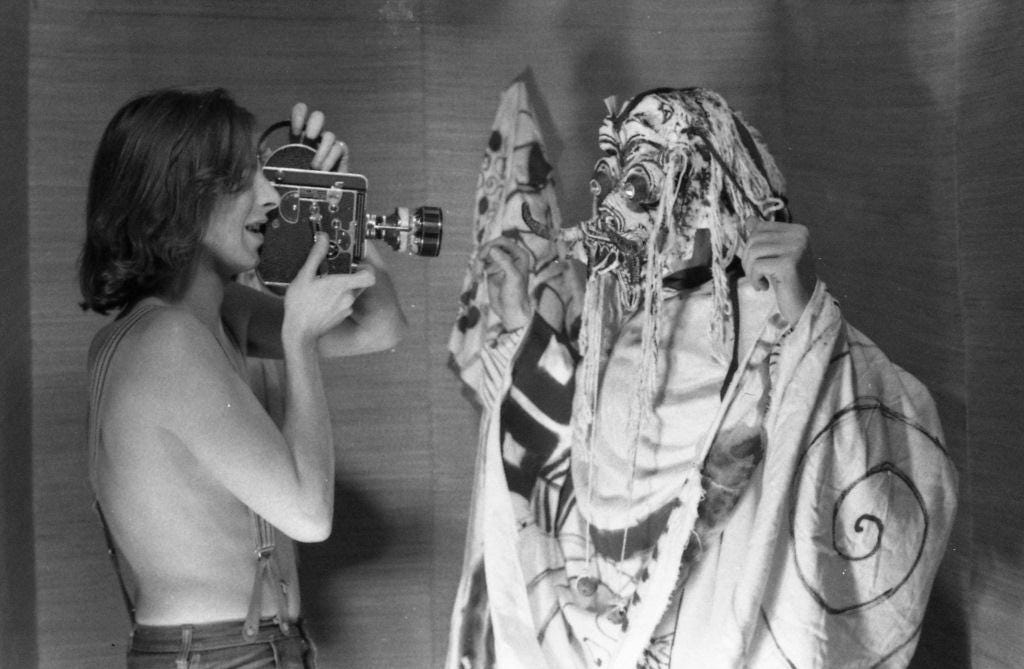

So, Redemption has put on the market new cuts, newly scored, of two films of a teenage Clive Barker, and, yes, they're very pure Barker. Salome, in particular, is Barker's silent adaptation of an Oscar Wilde play based on a tale from the Bible, and it is at once purely Barker, pure Wilde, and indefatigably biblical. The Forbidden makes an excellent argument for spectacle being content. There is a narrative to The Forbidden but there are more powerful and intricate narratives in you, in the audience, as the movie is experienced.

Barker's filmography since those shorts, his career in general, as been of spectacle, deification, wit and his audience's ability to generate the greater complexities internally, to be prompted by his work to do their own work even if theirs never leaves their minds and organs. I am not suggesting that they are watchable foremost for the purpose of study, but that study is going to be, perhaps, reflexive. Spectacle, by attracting attention, encourages meanings. You can't film someone having unreadable words transcribed over their skin before it is removed from their body in ritualistic fashion without the audience ascribing some meaning, even if it is a nonverbal and entirely physiological meaning. And, naturally, that is how it should be.

The best thing about teenage truths such a those revealed and enjoyed in the two movies, is that teenage truths are easy to see through and around without ceasing to feel the truth of them, the conviction and drive. Teenage truths, student truths, are somehow easily accepted as genuine facades, just as the fake skin we see peeled from a man (screenwriter and actor Pete Atkins) and feel it, accept it, even as we know that is a fiction. Truth in bodies, in exaggeration, in a refusal to present explanation, an insistence in presenting physicality and tease intensity, instead.