Boy Our Embarrassment

Go read at this link

Boy Our Embarrasment

then come back here and, read:

Somebody is mad right now – not even annoyed; mad – that I will not take a hard stance and declare what they want me to about Boy, the character in The Invisibles, her writer and creator, Grant Morrison, or the artists who have drawn her, the readers and critics who have discussed her.

For the sake of the book, There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles), I am treating characters partially as real people, partly as lesson objects, and then as fictional people, but that cannot mean I make too deep or radical of assumptions as to real people’s thought processes or beliefs while they handled and directed these characters.

And, I am not going to dive into whether I am more qualified, or qualified, to critique too hard the way Black women should be written, drawn, plotted or used in fiction. It would do you, Reader, no true good if I did.

No one who worked on The Invisibles is omniscient, nor audience.

I emphasize Boy’s use, as I see it, as a character and as an element in a comic which works as a workshop, because I can find a ready use there in talking about her. I think Boy is fantastic and I think Boy is problematic and I think Boy is used amazingly and I think Boy is given the short shrift.

Why do some people feel that Boy is misused? Or, poor representation?

Why do some feel they are bad representation?

I find it funny when nonwhite fans of Anne Rice’s fiction, for example, are treated as if they are naive of why it is problematic, offensive, or racist. As if readers are incapable of enjoying a horror novel while understanding that there is horror in it that, maybe, the author did not intend to scare. Many a reader can shudder at an old white man going on and on about the sexy fourteen year old Black girl with a myriad of descriptions of her skin color and softness all food metaphors and flights of erotic fancy, and still derive something useful from that shuddering.

When white voices orient white voices, even if the subject is nonwhite, what we really learn about is white people. How they speak to one another. How they talk to general audiences.

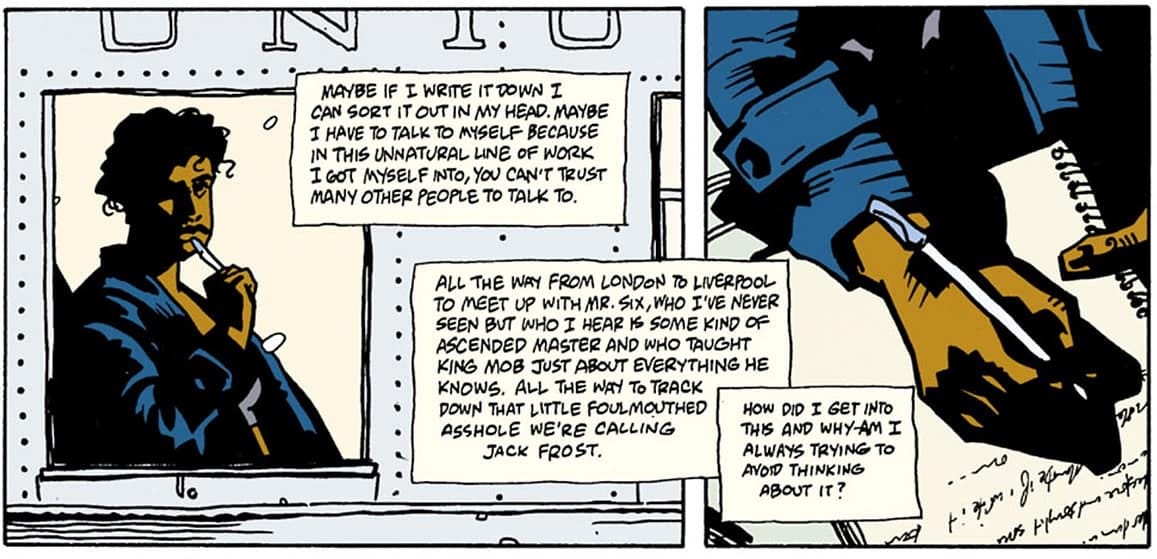

Boy feels she is poor representation. Surrounded, generally, by white people, some who exoticize her outright, a woman named Boy, led by men led by men led by men for several years. Boy doubts her soundness, her worth as a representation of the Invisibles, as a woman, a Black woman, spiritually, politically, as an American. It is easy for Boy to be humiliated or pushed into silence. Someone she just met making fun of her for reading Maya Angelou is enough to make her doubt her entire self.

That it is hardly dealt with in explicit terms, in the comic, and her removal from the narrative as soon as she has some of it sorted out, can be an opening for us to fanon in. Or, to accept that we and our ideas are part of a multiplicity.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Travis Hedge Coke to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.