Batman, Moses, and Donald Duck Walk Into a Bar...

Fictional Magic and Science

by Travis Hedge Coke

[Originally published Nov 27, 2014, at the Comics Cube, as a Pop Medicine column. Edited by Duy Tano.]

“Never accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice.” - René Descartes,Discourse on Method

“Magic I can take - I don’t like it, but ultimately it's just a science I don't understand. But mythology - gods — I like Thor, Cap, but his world — it violates everything I've ever believed in.” Kurt Busiek, George Perez, et al, Avengers vol. 3, #1

“The Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will.” - Aleister Crowley, Magick, Liber ABA, Book 4

Most of the time, we eyeball whether something is scientific or magic in a comic. We make a snap decision and our snap decision will probably never get challenged.

Distinguishing magic and science in a fictional setting is either done ignorantly or it is hard to do. Science, as a term, is fairly concrete in its definition, but not so in its practical, everyday use. The distinction is implied, it is understood, like drug versus medicine. Like “technology,” and like “magic” - whose proper definitions are also all over the place and often suspiciously lacking - “science” is a word we use most often to describe a feeling or a fuzzy set of general coordinates. Star Wars is a science fiction movie, Fantastic Four is a science fiction comic, in the same sense that people say “Batman is more realistic than the Flash” even though Batman stories have, more often, involved boojums and werewolves and Flash comics have, off and on, gone out of their way to include little presumably true science factoids, called Flash Facts. Batman feels more realistic, the way that Star Wars can feel more realistic than the same movie taking place without starships or circuitry. Unstable Molecules (Sturm & Davis) is probably the only Fantastic Four comic wherein all the science included is verifiable and functional, because it takes place in something very close to late 1950s America, but television sets and can openers in the late 50s does not feel of “science” the way rocket ships, alien’s with godlike power, and dimensional portals to an asteroid-strewn hell like the Negative Zone feel of science.

Why? Partly because science, in terms of the scientific method, or as a perspective, is political, in the same way that many churches or sects go out of their way to distinguish between miracles achieved by their own boys and home team deities and the (black) magic of the neighboring church or local doctor, lawyer, or cranky loner with a shack just past the edge of town who has all those fascinating things in jars and can do stuff with them. In terms of the English language, “magic” implies a falseness, a trick or lack of genuineness, to distinguish it from exciting Christian things that would otherwise seem to be cut from the same cloth, because otherwise it would be harder to police or belittle ones neighbors. The words carry more weight than they do definition.

The differentiation between magic and science, like those between magic and magick, magic and religion, or science and mad science, might as well be said to be primally a personal differentiation, because I’m going to prize human autonomy here and freewill. Authors are the intermediary between raw ideas or the world of influences, and the audience. While an audience is not required to interpret sympathetically with the author, what they receive in a comic (or any piece of art or story) has to come filtered and arranged via the author(s), and so, too, an author then has the central responsibility for what is presented, how it is filtered or arranged into art, into story or implication.

There is no genuine test for a person's conviction in God or a miracle, any more than there is a test for conviction in gravity or chickens. But, your personal understanding of those things, your understanding of their mechanics and their reliability can be so unconsidered, that as an author, you plug right along down a road without even realizing you’ve chosen the road from many, or that you’re electing to stray to one particular lane, at a generally stable speed, obeying both local driving laws and understood social niceties - even your road rage will occur and fall into socially agreed upon limitations and arrangements. This is true for a writer or artist portraying gravity as they believe in it, as it is for a writer or artist portraying St Paul, the Marquis de Sade, or Steve Ditko as they believe them to have been or the myths of them to be understood. Because we can do do that. We can distinguish between a Jesus Christ or Loki that we believe to autonomously exist and a Christ or Loki that we know others use as symbol or functionary in services or stories.

Christ and the Devil in Chronicles of Wormwood are cast in a modern perspective, because Garth Ennis is not producing a biography of either, but using them as characters and as pointing tools. They are semblances of things that Ennis knows are talked about, that he talks about, but which he does not believe in and cannot produce satisfactorily in some sort of flesh or brimstone or even with a nice halo and a good beard.

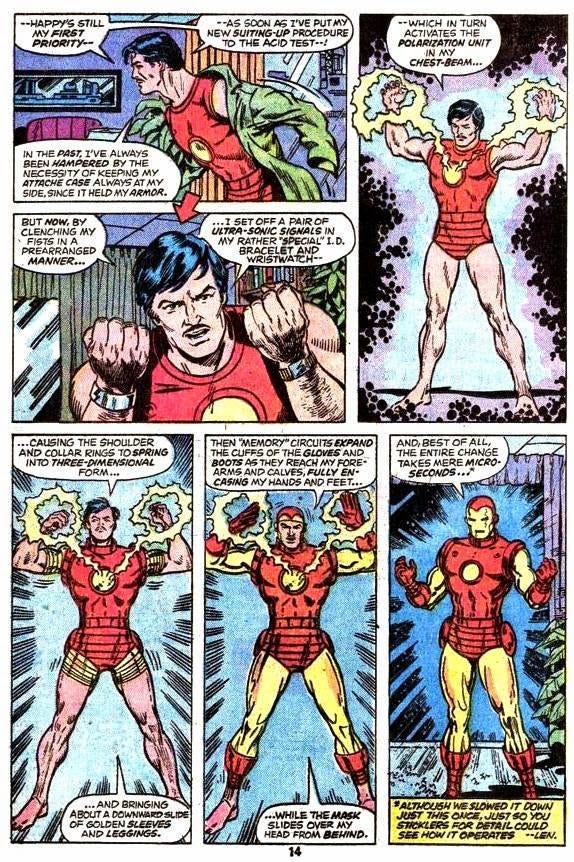

We have to rely on semblances in an agnostic or atheist story dealing with Jesus as much as Iron Man. What the Jesus iconography implies, it implies, and what the Iron Man iconography provides, is what we have to work with, both for authors and for the audience.

Can and cannot. Present and past. Science and magic.

Iron Man isn’t something, real-world, that is replicable or explicable in a functional way, but Iron Man is science, not magic. Society is not bothered by this assertion. Kulan Gath, however, is magic, because he is also full of powers that cannot be functionally explained or replicated in the real world, plus he is really old, tied to an old world, and wants that old world back. Magic, in a distinctly Anglo sensibility, is old and over there, unless we’re being “ironic.” Probably coming out of the rise of the Age of Enlightenment, and a cultural sense that magic, that miracles, have been lost, gone somewhere else.

You don’t see a lot of contemporary Chinese stories or Cherokee stories about how magic has gone off in a boat to a faraway land and all we have is cell phones and steak knives. Unless there’s a clear political underpinning, magic and science in manga that deal with both aren’t explicitly treated as a contemporary and ancient times dichotomy. This is an Anglo neuroticism from the Age of Enlightenment, when magic and miracles were aggressively condemned to the Past, along with such progress as forceps for baby delivery, a tool that legally only men were allowed to use, because… um… midwives… er… women are icky. Science! By which I hope, simply, to illustrate that this breakdown, this distinction, is not and was never one of rationality, but a political obfuscation which, in Euro-dominant societies, particularly Anglo societies, we've bought into through repetition and populism.

A Japanese story, a Brazilian story, wherein a wristwatch is somehow counteractive to magic, like it makes holy water explode or burns goblins, is pretty unlikely. Tempered steel counteracts magic in a ton of western European and Eurocentric fictions, though. Clockwork hurts faeries. Why? Because faeries and gods are old and like the past, in this view, they are trampled down beneath modernity. Modernity, in this model, is anti-magic and pro-science unless the author believes in the sort of magic being employed, which is where you get futuristic stories with full blown Catholic miracles or something likeThe Invisibles, which is explicitly wedding nominal magicks throughout an otherwise “real world” setting and future, because the author agrees with the bases of those magical orders and practices. Even as a generic rule of received wisdom or habit, steel being death to magic would be a hard trope to employ for someone who is aware of the ramifications of their own belief in, say, the transubstantiation of bread and wine into spiritual flesh and blood, the actuation of reality-altering energies through sigils, prayer or holy penance.

The Jesus or Hell that Ennis uses inChronicles of Wormwood or Preacher are not attendant to any personally-believed-in Jesus or Hell, but do draw considerably on ideas or previous representations of Jesus and Hell, because Ennis does not believe in an actual miraculous son of a god Jesus or a physical real world Hell. But, Evan Dorkin does believe in Abraham Lincoln and the Lincoln appearing in Bill and Ted’s Most Excellent Comic Book is, as well, shaped more out of the myth of Lincoln, the stories and portrayals of Abraham Lincoln, than what Dorkin (I’m assuming) understands to have been a real and verifiable man.Bill and Ted and Wormwoodare both fiction, and their President Lincoln and Jesus, respectively, are explicit characters. That, makes the difference. When dealing with an explicit character or place, we tend to be more conscious of how we use it, how we portray it, whether we believe in it or not. When we deal explicitly with places, people, ideas, we play not only to our personal understandings, but to our presumed audience; they are played for audience reaction. Thus, when we see the prominent religion of the audience dealt with in one of the big corporate-owned shared universes like the DC or Marvel Universe, we are far more likely to see sympathetic devils or varied representations of Hell, because those are traditional even inside Christian society, but an unsympathetic God or Christ is considerably unlikely, and indeed, even a sympathetic one.

So why do people have such a hard time separating Jesus, the ostensibly real guy, and Jesus, the obviously fictional character, when they can easily distinguish an obviously unreal Abraham Lincoln from the genuine article? The same reason we can buy Superman being powered by yellow sunlight and drained by red sunlight, but unaffected either way by yellow or red tinted light. Or, why we can accept Superman turning back time by flying faster that Earth’s rotation, against the rotation, but Superman singing the God of All Evil to nothingness might be too much. It is not about one being closer to reality or closer to science, what it is about is which one feels more genuine. In a sense, human history is towns laughing at the silly herbs and bone setting of the town across the river, and superhero fans scoffing at Superman singing evil to submission, while those towns use their own herbs, and those fans accept punching evil as a very real way to impede its progress.

Let us pretend that Batman is us, since we all know if we were just rich enough, dedicated enough, and lucky enough, with just the right dash of dead parents, we could be Batman. On the old TV show, and quite often elsewhere, Batman would accept anything at all as a vital clue. He would not analyze these clues critically or even pause to consider if it’s flagged by anything as a clue. Everything is a clue and the clues always reward leaps of faith and intuition with answers. We accept this as Batman accepts this, and the world he’s in seems to reward it. But, back when Batman first met Zatanna, a card-carrying daughter of a magic lineage, a sorceress, a witch, a spell-casting marvel, he accepts her accomplishments and tells Robin that they are not magic, but a genetic peculiarity allows her to access transformative energies from wood and other objects and direct it to miraculous ends. Like that makes sense.

Both in fiction and in real life, any investigator practicing this way would be a mystic, from Twin Peak’s Agent Cooper and DC Comics’ The Question to Matthew Fox or Hillel the Elder, but we do not see it thusly with Batman. Batman the “shaman” is isolated to a few Grant Morrison comics the same way that most of us, most likely, downplay our own personal mysticism and ungrounded suppositions so long as they work for us. Albert Einstein, who could just about be a patron saint of science, identified somewhat as a mystic, and he also famously rejected certain evident phenomena based on them, simply, not sitting right with him.

Which, roundabout, brings us to one o the most common unspoken distinctions between science and magic: Science is what works and magic is what cannot. In fiction or in reality, labeling either one, either way, cannot make them more or less workable, but, if Batman can explain the causal elements of a magical act than, by this distinction, it is now science. Magic that works, like science that works, are not obfuscations, but technologies. At least, this is true in-world. In-world, if someone can do something via magic-sounding technologies or science-sounding technologies, than it is a genuine thing with some ability to describe its functions and replicate them. As an audience, though, we are not receiving them as technologies, but as a symbol of functionalism, of accomplishment. The last minute save, in fiction, is not very different from divine intervention or answered prayer; these forms of desire trumping expectation are rewarding in the same fashion, but what agent the act is ascribed to has a social and personal effect that is different from the one experienced by anyone in-world.

I don’t mean to qualify either “side” of this as superior, and I realize I’m expanding this beyond comics, but it might be impossible to overestimate how much this affects comics. A christian who is not explicitly dealing with their version of christianity in a story, may wholly believe they are not addressing christian beliefs or expectations in the comic, but these expectations become nearly invisible to an author when channeled implicitly. Our self-corrector, our social-adjustment software, so to speak, bypasses the expectations and structures, the same way a metal detector that would identify a pistol, but not discussion of pistols, even if the discussion is, “Hey, I’m going to bring a gun in tomorrow and…”

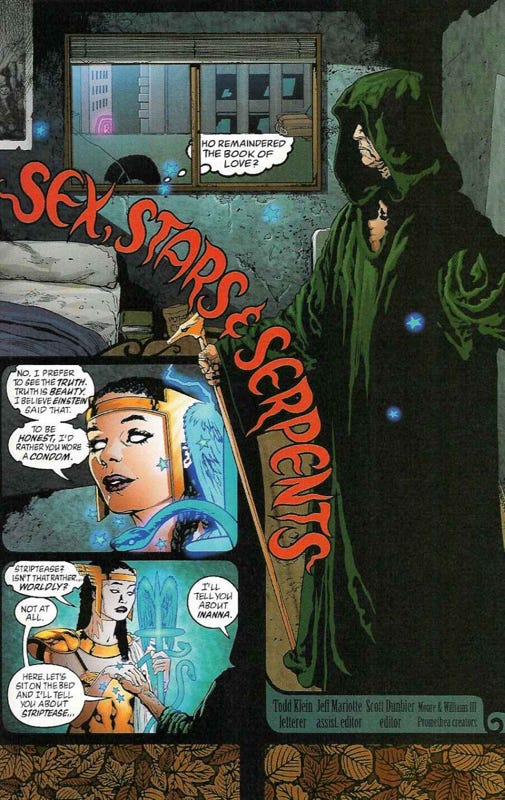

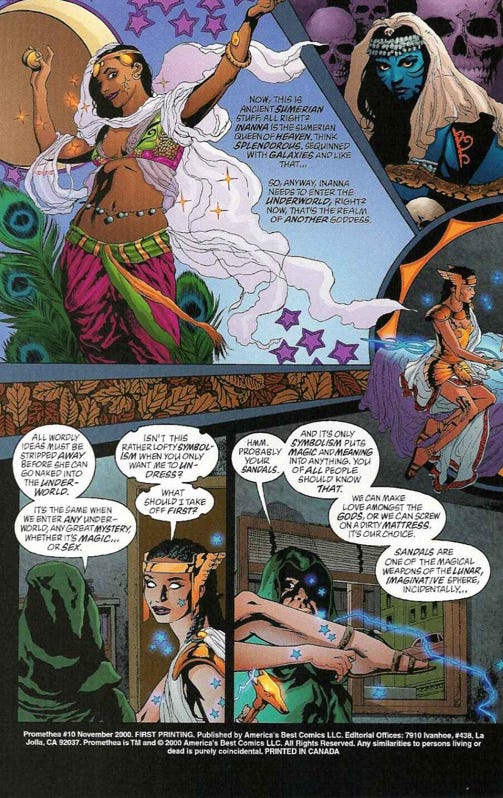

Both authors and audience stop questioning readily when the structures are implicit. But, because an author predates the audience appraisal of a comic, the audience’s alarms can be set off by something implicit that does not agree with their mysticism, their moral or world order, their idea of how things work and why. The authors are, in essence, gone by then. They might read a review that enlightens them, or an editor might call it out, the artist might question the colorist, the colorist might question the writer, but that, generally, occurs before the product is out there in the world. Audiences, though, can be moved to disruption. Audiences can be shocked or dismayed. It isn’t the explicit characterizations and actions, the causes and effects or personalities in Promethea that set my teeth on edge, it’s the moral ordering, the behind-the-narrative lessons and moral causation.

This (abridged) sequence in Promethea, between our heroine, her highest spiritual self, and a cruddy old misogynist who only recently was presenting himself as a sexy younger man, screaming in her face, and trying also to murder both our heroine and her BFF

is part of Alan Moore’s effort to express what he considers very serious magical and social ideas to his audience, and… it’s all kinds of fucked up. I won’t even make apologies for that, and I have been known to make apologies for the teenage love interests in Woody Allen movies.

An astute reader may have, by this point, decided that I don’t see a great deal of difference between religion and magic, or feel that there is both a religious and a separate secular moral framework to an author’s mind. That’s part correct; I don’t believe there is any difference. What Alan Moore is expressing is both a lecture on magic using a story to get it across, it is also a moral and causal framework, a How Things Are explication. How They Should Be. How They Work. The “cuteness” of the banter regarding undressing or the wise old man’s leering bragging cues us to implicit understandings, to an implicit framework, even while there is explicit magic in the transfiguration of Sophie into Promethea or creepy old guy’s ability to cast glamours at will. The causation, here, is no less religious/political than, to take this further into the realm of implicit religious moral ordering, the scenario that Chuck Dixon, himself, describes in the Wall Street Journal as, “Chuck, expressed the opinion that a frank story line about AIDS was not right for comics marketed to children,” without also noting - presumably because he does not connect them - that Dixon was at that time doing stories for those same comics involving underage pregnancy, or positioning the rich, white American, Tim Drake, as a sort of “everyboy” character who was ethically abstaining from sex and consistent in impishly downplaying the young women in his life as a sort of secondary citizenry. These, too, are affects of a moral ordering, of a religious/political outlook.

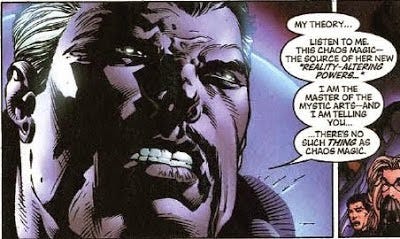

Those religious/political precepts, which are not backed by rationality so much as habit, and therefore generally do not qualify as “scientific” suppositions or causalities, go much more easily unchallenged than, say, a comic where Heaven lands in Idaho and God’s a bit of a drunk, but it’s okeh because Jesus and St. Paul can throw bolts of radiation from their eyes and hands. You can’t prove either one, that young rich white American boys are always right about everything just because they have drive, or that St. Paul can’t cast beams of energy from his eyes. In point of fact, most comics readers have no problem accepting a myriad of demons and devil-stand-ins, but also things like Hades being an “evil” god, Loki being someone who “isn’t worshipped on Earth any longer,” but even too, Ganesh, as a deity “of the past” who can probably throw lightning from his tusks. Comics readers who took issue with Grant Morrison using angels in their JLA comics, despite that being generally respectful and decently researched, probably didn’t blink too hard when Stephen Strange, master of the mystic arts and the universe’s Sorcerer Supreme said, “There’s no such thing as chaos magick.”

It’s not about fairness, or faith, or rigorous study and conviction. The distinction between magic and science, religion and magic, can and cannot, especially when implicit, and in pop comics (and other pop media) boils almost instantaneously down to what we have socially agreed upon to unblinkingly let slide.